|

| The

Qaanaaq Region |

| Upernavik

to Qaanaaq : Previous leg << News

Index >> Next episode : to come

|

|

Chart of Harward Oer and Qeqertat (© Kort & Matrikelstyrelsen,

Miljoministeriet, Danmark) |

Autumn 9: It's

dark (November 30th, 2015)

If you can read this message, we have re-established communication

with Qaanaaq. Since nearly three months we have been cut off

from the world. The absence of infrastructure has impeded

any communication with the outer world during the period in

which the ice was forming.

This lack of communication did not stop us from filming,

taking pictures and writing about our experiences. With more

or less delay you will be able to discover the period in which

Nanuq transformed from sailing yacht 'umiaq' to 'igloo' and

got frozen in by the ice since our last post on the September

28th - 'immaqa' - in chronological order:

It is dark ...

... the temperature has dropped bellow -30°C. The average

temperature for the winter months in Qaanaaq is -25°C;

in Qeqertat it is two degrees less than in Qaanaaq and in

'Nanuq's Cove' three degrees less than in Qeqertat. The full

moon, which never sets, gives us a day without night. A thin

layer of powder snow, which shines and sparkles in the light,

covers the landscape: Blue Moon! Magic!

Nanoq - the polar bear - has been seen several times in the

West. It's the fifth that tries to make it's way up the fjord.

We double our care. Accompanied by Sara, our dog, a gun and

powerful headlamps we venture out to explore the region in

this new light. Tomorrow we will transfer part of our dog

food onto the ice, a short distance from the camp. This will

allow the bear to have a feast and leave us alone, at least

for a while.

The outside work is finished. We have installed the weather

station that measures and logs meteorological data: wind,

solar radiation, albedo, air and water temperature and the

heat flux that goes through the ice (see science

page). The batteries that were intended to supply the

installation with electricity do not resist the cold. Therefore

we have moved the station close to the boat (50m) and connected

it to our main electrical system.

Twilight at miday: Nanuq and the weather

station (photo Kalle Schmidt)

Everything is ready to welcome the cold. The excellent thermal

insulation and the relatively warm temperature of the water

below the ice-shelf provide a thermal balance requiring very

little energy to make a comfortable dwelling. During the 'day'

the heating works intermittently to maintain a pleasant temperature

inside the cabin. When we sleep, the heating is turned off,

activities stop and the temperature progressively establishes

itself around 5°C in the cabin and 0°C in the sleeping

quarters. The warm sleeping bags create a warm and cozy bubble

around us and guarantee a good night sleep - no need to fight

to keep warm.

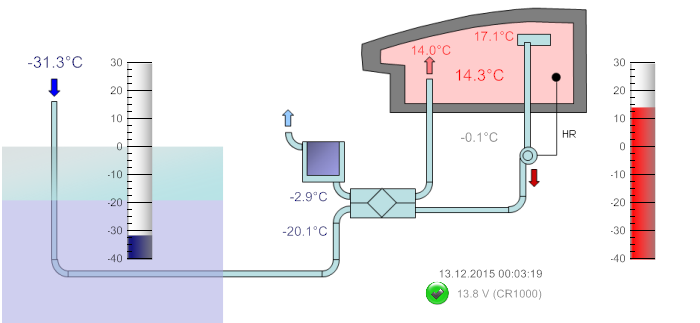

The heat recovery system is most amazing. The screen shot

below shows mesurements on a typical day (-30°C). Supply

air enters the cabin at almost indoor temperature, using only

a few Watts for the ventilators. The fresh water condenser

has not been installed due to the close to zero exhaust air

temperature and easy supply of fresh water from the nearby

lakes, as long as available since ice is getting thicker every

day...

The passive igloo project - screen capture

of RTML interface (Logernet). Fresh air (-16.2°C) is preheated

through an imerged pipe in order to reduce icing of the counter

flow heat exchanger (-10.1°C). A humidity sensor (HR)

controls the air change rate. The fresh preheated air is intruduced

into the cabin at close to heating temperature (16.8°C).

Exhaust air quits the boat at close to freezing temperature

(1.3°C). (by Peter Gallinelli)

With the arrival of the cold, the 'passive igloo project'

gets to it's operational stage. The goal is to spend an

arctic winter in complete self sufficiency and without use

of non-renewable energy sources, to explore the possibilities

and the limits of the passive dwelling of tomorrow. The objective

is not to achieve this goal with unlimited resources, as this

would be an exclusive luxury. Instead we try to drastically

reduce dependence from non-renewable energies exploring robust,

affordable, simple and comprehensible solutions.

'A good solution is a solution one can forget about'. Although

it is still too soon to draw conclusions on all the systems,

the reinforced thermal insulation is without a doubt part

of the good solutions.

Our fuel consumption is minimal considering the biting cold,

the absence of wind and the simplicity of the systems: an

excellent insulation, a wind generator and a heat exchanger:

50 liters for one month of comfort. Heat pump and warm water

storage had to be abandoned due to our tight budget. A first

analysis indicates that over the past month, the primary energy

consumption has been of 250W/person. This energy is used for

heating, lighting, electrical equipment, warm water and cooking.

This is 10 times less than the swiss average. And we are in

the arctic with an average temparature of close to -20°C!

Above 0°C (the average temperature in January on the swiss

plateau) the heating system, also the biggest energy consumer,

is no longer needed. The coming winter will allow us to study

and learn about how these systems perform in the long run

in very cold conditions. And we are looking forward to it!

Blue Moon: full moon (or nearly) over

the ice. Nanuq is in her element. November 25th | 77.5°N

| -25°C (photo Kalle Schmidt)

Hence we are heading into the cold, gloomy and magic arctic

winter. This will probably be our last message before the

end of the year. It will begin its voyage tomorrow when we

visit the village; a road with many uncertainties. Our home

is onboard Nanuq, no possible return.

So we look ahead, towards the adventures to come. We still

have to install some sensors that will do an objective observation

of what we live in a perfectly subjective manner. The two

methods complete each other. We are here to learn about the

dwelling and its inhabitants - us - in an extreme

environment.

For us, Team Nanuq, the idea of passion is about experiencing

new colours and flavors, discovering new places, meeting new

people, being in close contact with nature and exploring our

own limits. What

drives us is the possibility to experience, the urge to try

new things and the curiosity to understand - and this is exaclty

what we do.

The ongoing challenges are:

- Sleeping patterns - our natural rhythm shifts later 45min

per day...

- Energy management with no wind at all (10 days+)

- The communication with Qaanaaq and the rest of the world

But, everything goes well onboard :-)

We wish you joyful Christmas period and a beautiful winter.

Bai- takussagut (*)

Peter & crew

(*) Kalaalit ('baï takouch') = see you soon

Autumn

8 : Work on the ice (November 20th, 2015)

The barometric pressure drops drastically and we experience

the third storm from the South. After a period where we got

a small taste of winter (-20°C) and the first northern

lights, the sky is low and the wind blows with gusts up to

50 knots. The temperature is positive. The wind brings temperate

air from far away. Free from landlines, Nanuq rests well protected

in her frozen cradle. The gusts make us heel a few degrees,

hardly noticeable. Our 'mooring' is perfect!

Rigid like a piece of metal sheet a few days ago, our dinghy

becomes soft again, and we take advantage from the warm conditions

to fold it and store it away. Now useless, it was of great

use to us during the periods of high tide (approximately 3

meters during spring tides), as the ice close to the shore

was not as developed. As for now we can cross the delicate

zone jumping from one ice cake to the next, making sure not

to sink into the soft ice in between.

We have finished installing the prototype for the ventilation

system. On the one hand there is the need for oxygen inside

the cabin, on the other side there is humidity which has to

be evacuated. Otherwise the inside of Nanuq would fast turn

into a humid and uncomfortable 'cave'. Uncontrolled ventilating

would lead to cold air invading our haven of heat. Therefore

we use a heat recovery system. The system uses the heat from

the sea water (-1.5°C) to preheat the much colder incoming

arctic air (-20/-40°C), which will then, by means of an

heat exchanger, be heated by the inner warm and humid air

which is to be evacuated. The regulation of this process is

done according to the inside air humidity. It is a good and

simple indicator of human presence and activity inside of

the cabin. And it works splendidly! We are curious to learn

from future experience.

Our visitors are intrigued by the installation half way between

technology and tradition: the “buried” pipe is

submerged 2m under the ice in the same manner as a fishing

net, held by small strings attached to ice clamps (can be

seen on the picture).

Work on the ice: installation of the

“buried” pipe used to preheat the incoming air.

The bloc on the right is used to hold the air intake in place.

It gives an idea of the ice thickness at the time. With the

cold the blocs freeze together. (photo Kalle Schmidt)

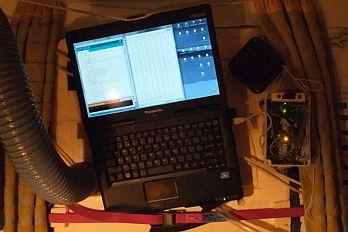

Work with the headlamp: with a cloudy

sky, there is only a very slight twilight. On the right: in

front of the heat exchanger, the computer and the micro controller

that control the ventilators and the system that prevents

condensation inside the system from freezing. (photo Peter

Gallinelli)

The challenges for the moment are:

- Humidity inside and around the boat - salty environment,

drying, condensation, cold spots

- Hygiene and laundry - washing and laundry need a lot

of energy and water, and produce a lot of humidity

- Food - “good food brings good mood” and vitamins

are important, even with a limited resources.

- Energy - managing our limited energy supply due to very

slight winds.

Today there is abundance. There is plenty of wind and the

wind generator turns at full speed. We manage to heat and

completely dry the cabin with small electric radiators. We

have had a period of relative calm, so we are enjoying the

situation. We are counting on a weekly load to keep our batteries

charged…

The transition is complete. Nanuq is ready for the winter.

Autumn

7 : Twilight in Qeqertat (November 7th, 2015)

We experience another Sunday in the paradise of ice. Our

universe does not stop transforming itself. As by now the

day has become twilight. For the past days, the thermometer

has been indicating -20°C and continues dropping. The

ice grows fast at this temperature and we can now move freely

across the bay. It is time to get our legs used to walking

on the slippery ice. We discover muscles we never thought

we had.

Walk on the recently formed ice: 20cm to safely move on the

ice. (photo Peter Gallinelli)

With the fresh ice we are happy to receive our first visits

from our friends from the village! Our crew has increased

with the arrival of a new member: Sara, the dog that the young

girl from Qeqertat by the same name borrows us for the winter.

She and her father come regularly to join us for “kaffi”

onboard. It’s a great opportunity to improve our Greenlandic!

Hunting and fishing on the ice has started (photo Kalle Schmidt)

We join Thomas to install his seal net and are impressed

by the simplicity and efficiency of his device; no tool is

excessive. We witness a life illustration of a quote by Saint-Exupéry:

“It seems like perfection is achieved not when there

is nothing more to ad, but when there is nothing else to be

taken away…”. E = mc2 was not written in one day.

Identically it took many generations of hunters to perfect

this technique. We have a lot to learn from these astonishing

and loveable people.

Scientific programme: installation of the PCBs on the ice

(photo Kalle Schmidt)

This Sunday we install the PCB absorbers. The material, prepared

by the the University of Savoie,

is easy to install even with biting cold. To attach it to

the ice we pour liquid water on the feet of out poles, which

freezes immediately - in the same way as the locals! The installation

will stay at the same place during the whole winter. The analysis

will be done next year, on our arrival in Europe.

We have prepared the “pulkas”. They are much

appreciated to transport the precious drinking water that

we fetch in one of the numerous lakes 1km away froth boat.

It is far more efficient than carrying 80kg on our backs.

After a day outdoors, we welcome the comfort onboard Nanuq;

a warm tea and a large meal to reconstitute the calories burned

before.

Nanuq in her ice cradle - November 8th.

The rudders are tilted upwards to avoid being exposed to the

pressure of the ice. (photo Kalle Schmidt)

What does the arctic night look like?

You may try to imagine the arctic night with interesting

information concerning sunrise, sunset, moonrise, moonset

and twilight in the tables here below.

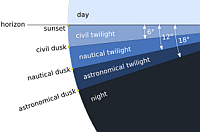

There are 3 types of twilight:

image

from Wikipedia image

from Wikipedia

Civil Twilight: from sunset to the time

at which the sun is 6° below the horizon. At this time,

there is enough light for objects to be clearly distinguishable

without artificial illumination. Civil twilight is the definition

of twilight most widely used by the general public.

Nautical Twilight: the time when the centre

of the sun is 12° below the horizon, and only general

or vague outlines of objects are visible, when it becomes

too difficult to perceive the horizon. This term goes back

to the days when sailing ships navigated by using the stars.

The use of a sextant to measure the altitude angle of stars

required horizon visibility.

Astronomical Twilight: the time at which

the sun is 18° below the horizon. It is that point in

time at which the sun starts lightening the sky. During the

evening, this is the point where the sky completely turns

dark.

Light is of course only available when the sky is clear...

Source of data : U. S. Naval Observatory, see http://aa.usno.navy.mil/data/docs/RS_OneYear.php

Autumn

6 : Here we are (November 5th, 2015)

This our planet...

Icescape with full moon: it doesn't

set; it points us to the North (photo Peter Gallinelli)

The beginning of November marks the last sun. Most of the

day is lit by twilight. The days, being shorter each time,

are an always changing spectacle of pastel colours. The cove

where we are moored in is now completely frozen in. We have

the feeling that we have landed in some remote crater somewhere

in the vast Universe. Nanuq looks like a stranded spacecraft

on an interstellar voyage. Equipped with ingenuity and resources,

she allows us to live in this hostile and exceptional environment.

10 months of solitude separate us from the moment when the

ice will clear and allow us to move into open water again

and make our way back ... towards our world.

The temperatures vary between -10 and -20°C. A freezer!

We work outside huddled in warm jumpers, jackets and dry-suits.

From far away, equipped like this, we look like astronauts;

except for the lack of breathing equipment, for we are lucky:

the atmosphere of our planet is breathable.

Nanuq securely moored in 'Nanuq's Cove'

- watch out for the drying rocks in the middle of the bay

(photo Kalle Schmidt)

The feeling of loneliness is overwhelming. Except from a

rescue operation there is no way back. Until the ice is strong

enough, we live in some kind of isolation from the outer world.

We rely on our resources. The voyage takes a turn towards

becoming an autonomy lab - everything has to be done with

the limited resources on board and what nature is willing

to offer. The only unlimited resource is our creativity.

For example, the notion of waste has nearly disappeared.

We don't have much space to store it anyhow. But also, these

materials can be useful in many ways. A light bulb in a jam

glass becomes a source of heat to keep our compost warm. An

insulation panel becomes a polyvalent building material. Many

parts and pieces come from reutilizing what we might no longer

need or others have discredited as useless. Slowly, through

necessity, we learn the art of doing more with less so familiar

to the Inuit culture, capable of transforming with genius

simple materials into objects with an exceptional value. What

a contrast to the consumerist world, which throws away!

Even the exhaust air from the cabin is recycled. A few days

ago we installed our heat recovery system. The heat and the

humidity from the inside air become a valuable resources.

The water, which is formed through condensation inside of

the heat exchanger, rejoins our fresh water supply, very valuable

in the arctic. The heat from exhaust air is used to pre-heat

the fresh cold air coming in from outside. A micro-controller

is in charge of regulating the air flow by ventilating no

more than is needed and of keeping the heat exchanger free

of ice. This equipment is one of the developments made for

the passive igloo which will undergo testing during

the winter. The only thing that is left to be installed is

a thick hose to preheat fresh air from the outside through

seawater. Below the ice, the seawater temperature never drops

below -2°C - rather warm when it gets really cold: -30°C...

Passive features, such as thermal insulation or low-e glazing,

are so efficient and discrete that we almost forget them.

They are simple and essential parts and the expedition would

be impossible without!

To be continued...

Autumn 5 : Harward

Oer - the freezing sea (October 28th, 2015)

Slowly Nanuq transforms from the Umiaq, the boat,

to the Igloo, the home, as the Inuit call their dwellings.

Installations, rearrangements and cleaning up fill up most

of our days. Our TODO-list becomes shorter each day.

We also make surprising discoveries: some condensation has

appeared in unexpected places. We add insulation to these

areas as well as we can. Therefore our ventilation system

takes an even more important role, as well as keeping vapour

sources under control: cooking, washing and ourselves.

Our vessel, stranded on a wild planet

- Nanuq in the arctic (photo Kalle Schmidt)

The big wind generator has found her place on deck. She has

started to produce her first kWh. We are marvelled to see

this machine transform wind, an unlimited natural element

to our disposition, into precious electricity. We wish for

abundant wind. Are we at the right place for our hopes to

come true? The little data concerning wind patterns do not

allow us to make a reliable forecast. We will have to adapt

to what we get, whether it'll be as we hope ... or the opposite.

Our fresh food supply is slowly coming to an end and now

creativity is asked for! We have dried pulses, rice and starchy

food as our basis. It is time to create nourishing and varied

dishes with our limited ingredients. Except for rare occasions

we have eliminated pasta - popular dish as it is appealing

and easy to prepare - since it uses far to much water and

energy to be prepared, as well as producing tons of vapour.

We prepare different soups with beans, lentils, and chickpeas.

They are easy to be prepared in our pressure cooker. The only

thing we have to think of is putting them into water the day

before. Seems not to much to ask! We rediscover an ancient

art of cooking, a delicacy. To give a range of tastes to our

ingredients, we appreciate the different spices we have in

considerable quantity.

Every Sunday we bake 2kg of fresh bread for the week - a

moment in which our igloo fills with the delicious smell of

freshly baked bread and becomes cosily warm due to the heat

produced by the oven. For bigger occasions a cake or a pizza

is added for a change. Except for the lack of fresh vegetables

and fruit, our menu lacks of nothing from our terrestrial

cuisine. The time for fishing has not yet arrived. But soon

the sea below the ever-growing ice will provide us with the

ingredients that constitute the base of the traditional Greenlandic

diet.

Ice - at last! Nanuq becomes the 'igloo'

(photos Peter Gallinelli)

Thickness of the ice: 15 cm. We are temporarily restrained

from our visits to our friends in Qeqertat as we don't dare

to play icebreakers with our inflatable dinghy. The ice allows

us to take a few steps around the boat, with care and always

in company of our dinghy that we pull behind us, just in case

the ice should not hold our weight...

Autumn

4 : Stormy Bay (October 25th, 2015)

Tonight we have not closed an eye. Ready to jump out of our

sleeping bags we take part in the spectacle given by mother

nature: a symphony of whistling in the rig, the hull scraping

in her ice cradle and bumping against the edges, cracking

of breaking ice, a loose band whipping the deck, an object

sliding when the boat leans with a strong gust, the landlines

solidly installed around rocks cracking on their clamps. Big

clouds of snow and dust pass over our hatches. From time to

time we switch on the deck light to check that we do not drift

away - we don't know yet how boat and ice behave - also to

check if our dingy is still there; we have fastened it upside

down on leeward of the boat after it tried to fly away a few

times - it seems to be behaving now.

Arrival at 'Stormy Bay'' (photo Kalle

Schmidt)

It's just one more of the southerly storms that leash their

force on this region. We were introduced to them during the

first days in the apparently sheltered bay, which we originally

had thought as being our winter camp. We had been warned about

strong winds on the ice cap. The wind speed for our region

was forecasted to be 35 knots, a gale easily handled. We believed

it for a moment: two anchors and two landlines seemed perfect.

...our opinion changes drastically when the first gusts arrive

as if Thor had swung his hammer at us himself. Just in time

we let go the landlines and the anchor, to moor a little further

into the bay. It was then that the real storm began. In spite

of the excellent hold of our anchor, it becomes impossible

to resist to more than a few gusts before it would leash.

Gust after gust, easily 60 knots, fall over us. The strongest

gust exceed 70 knots - our mooring stands no chance. We start

the engine at once!

It's dark around us. We take down the mizzen sail, otherwise

it will be torn away. The wind howls and it is impossible

to communicate on deck. The only way the other hears is by

shouting at full pitch 2 m from each other. Without any sail

surface, Nanuq heals at each gust. The side deck dips into

the water. The visibility is only a few meters. Everything

is white. The wind has become a hurricane. It tears the water

from the sea which has transformed into white foam. The limit

between air and water is uncertain. We are on deck, soaked

to our teeth, making rounds on the water while waiting for

some calm. We are not eager to end up on some shoal and spend

the winter there.

Although the wind doesn't give us a single moment of rest

there are some advantages to our situation: the warm temperature

(0°C); these wind conditions in lower temperatures would

have been much harder, the full moon allows us to see the

shadow of the coast in the dark and our little bay is well

protected from the open sea. After a strong gust, we just

have enough time to make our way towards the wind beating

backwards. Luckily Nanuq has no hard time of sailing against

the wind, which allows us to reposition ourselves after especially

darting gusts. The diesel engine runs smoothly as if nothing

was happening. Reassuring!

With the first daylight, the wind turns to the South, allowing

us to moor ourselves back to the landlines. It is a delicate

but successful operation. As soon as we are belayed on our

port clamp, another gust falls over us. Nothing happens, we

are at the same place as before: oufff! Now it's time to recharge

our batteries. Adrenaline is an amazing resource. Whereas

we did not feel tiredness, hunger or cold while on deck, now

we have to rest. We sleep, keeping watch in turns. The gusts

become less strong. Only a few set off the alarm, which is

set to 60 knots. As the day goes on, the wind slowly settles.

We look at the disaster on board: pillows and other objects

lay in all possible corners, a bowl of spaghettis paints the

cabin floor in Italian colours. The contents of the drawers

that weren't properly secured lay scattered around. The anchor

and chain shine brightly, polished by the ground of the bay.

But Nanuq and her crew are solid - not a single scratch. Only

the cairn built ashore the day before has disappeared!

Our mooring at 'Stormy Bay', the day

before the storm (photo Kalle Schmidt)

With what we have seen this night, everything we feared for

before seems to be of no importance. We change tactics: we

become nomads again and will have a North and a South mooring

where we can retreat to, in case a storm approaches. We continue

to explore our surroundings and discover a perfect, tiny bay.

We ask ourselves if it has not been our wish that has led

to the existence of this place, which we had not seen two

weeks earlier when we passed close by.

Nanuq is now securely moored with two solid landlines to

the North and two to the South. The length of our full mooring

material is just enough! We have no desire to do rounds again

in the chaos of a storm, which without doubt will come...

|  Moorings

Moorings

Harward Oer 77°29.5'N 66°33,5'W : there are

numerous mooring possibilities in this natural harbour

which is situated between the two main islands of Harward

Oer. The bay we unofficially call 'Nanuq's Cove' can

only be used with landlines. Protection from S-ales

is good, from the North slightly less. Winds from E

and W are moderate. There are several drying rocks in

the center of the bay. Further inside the ground is

not deep enough. Therefore it is convenient to attach

two landlines to the N and two to the S, close to the

entry of the cove. Strong straps (such as used on cargos)

are perfect to make a good anchor around big rocks.

200m of mooring line are advised. The depth in the entry

is around 3m. There is a deep lake at about 1km to the

SE, with clear fresh water to fill up fresh water tanks.

The landscape is breathtaking with many different hiking

possibilities. The distance to the village, Qeqertat,

is 2.5km in a straight line, but you need a dingy to

cross the bay (if not frozen).

Spring tides are of about 3m, half for neap tides. |

Qaanaaq

region : 77° latitude North © worldwind

NASA bluemarble 2014

New

photo walls (September 28th, 2015)

Nanuq moored close to Qaanaaq as seen

from the Hotel

Qaanaaq (photo © Hans Jensen)

A last share before leaving Qaanaaq ...

Cheers,

Peter & crew

Autumn

2 : The last straight line (September 26th, 2015)

Stormy night in Qaanaaq. The gusty wind form the N blows

with up to 40 knots falling down the steep hills over Qaanaaq.

The mooring is exceptional, fortunately the ground has excellent

hold. Thanks to our 40kg anchor and 50m of 12mm chain, the

boat takes every stormy gust and our igloo stays a haven of

peace faced against the wind and weather. The nearly full

moon shines a dim light on the icebergs that slide by our

window down the fjord and the dust and snow is blown of the

hills against the twilight.

Two cables ahead the lights of Qaanaaq glow with encouragement.

Yes, this improbable place is well inhabited. Hostile at a

first glance, these two weeks that we have stayed here have

made us understand what it is that people appreciate here.

Without doubt, we are facing one of the most beautiful views

of the world. Hans Jensen, owner of the welcoming Hotel

Qaanaaq confirms this to us - the view from the Hotel

is exceptional. Regarding the organisation of the day to day

life, it is done without rush and with respect towards the

natural rhythm. There is no reason in rushing one step ahead

or to force the impossible. Here time is taken into consideration

and there is always a moment for community.

First ice forming on the sea-water - early pancake ice - nanuq

(photo Jakob Gallinelli)

We feel welcomed and we try to honour te welcome that is

given to us by giving back as much as we can. The opportunities

are numerous to exchange and learn from one another, be it

while buying supplies, organising the rest of the stay, visiting

the school, etc. And so friendship comes to be. We are very

grateful for this kind welcome from these friendly people

of Qaanaaq, the uncountable times we have been helped, and

all the good advice that we have received all along our way!

Yes, this country-continent (much more than just an island)

is magical, its geography as well as its people. We have much

to learn.

Greenlandic tradition: collecting ice to produce drinking

water from pollution-free thousand year old ice (photos Peter

Gallinelli)

Yesterday we received the good news: we have the green light

from the government and the local authorities to install ourselves

for the winter on the Greenlandic territory, here in the Qaanaaq

region. As for now, the road is clear: except for the last

correspondence with the rest of the world for some time, everything

is ready. The internet connection that has allowed us to reach

out to everybody will be cut for long months to come. A true

detox awaits us. We have learned to be autonomous - nonetheless

we will have to rediscover the use of paper post, which will

be delivered by dog sledge, and what it means to wait for

a reply. But don't worry, the blog will be kept up to date

by a combination of technology and old school techniques:

a memory stick in a letter! That way we'll keep you up to

date, like a friend of ours said: 'it's a kind of combination

of the old fashioned way and modernity to achieve efficiency'.

And going the other way - you may write a few lines here.

Very soon Nanuq will moor her anchor in a perfect little

bay on Harward Oer. She will transform into the igloo she

was designed to become - in the true sense of the Greenlandic

word: our home. The ocean swell, the gales and the uncertainties

of navigation are over for this season. They give place to

a new chapter, the apprenticeship of the cold: a long open

road that we follow forward; under the watch of the inhabitants

of the region, who warmly welcome our initiative. An opportunity

to live life...

Those of you who read these lines, we wish you a beautiful

autumn and we'll talk to you through the next post in some

time.

See you soon,

Peter & Crew

Autumn

1 : Inglefield Bredning - Queqertat (September 15th,

2015)

Bowdoin Fjord, end of season, Qaanaaq region, Greenland (photo

Peter Gallinelli)

If you can read these lines, it means that we have arrived

back in Qaanaaq and the 3G connection works, unexpected but

appreciated! We hope to be able to stay overnight at this

exposed mooring in front of 'the capital' for our last technical

touch down before heading to our winter camp...

Nanuq mooring at Harward Oer (70°30'N); sunset after the

snowfall (photo Peter Gallinelli)

Ingelfield Bredning, 80 miles long and 10 miles wide, is

the biggest fjord in the NW of Greenland. Covering a surface

as big as Switzerland, it is home for about 800 people settled

in a handful of villages, Siorapaluk being the northernmost

in the world. 600 live in Qaanaaq - an artificial town installed

by the American army in the 50s to displace those living in

Dundas and Pitufik. The main activities of the local population:

hunting and fishing...

Qaanaaq is also a crucial point for many expeditions. We

meet Hans Jensen, the owner of the Qaanaaq Hotel. On the walls

of his establishment he shows us endless pictures of expedition

teams who stayed with him for a few days. We find nearly everything

we need, but we have to anticipate. The supply ship only passes

twice a year. Right now, the Arina Arctica lies anchored

before the town. The lighter travels back and forth between

the cargo and the coast unloading two containers at a time.

It is a long process as they can only work at high tide. The

inhabitants are joyful: new stocks for the store and for some

there is even a new outboard motor. The empty containers and

used machines are ready to travel back to Denmark.

Anchorage at Kangerdharssuk. First snow September 11th, 2015

(photos Peter Gallinelli)

After a technical stop and with the permission of the local

administration we start our exploration of the fjord. The

temperature has dropped below 0°C. The wind blows and

it snows. The landscape, mineral and coloured, is now covered

by a white blanket. Winter magic! The helmsman, watching out

for drift ice, is warmly dressed with warm clothes and a ski

mask.

Helmsman in the snow. Rock formations close to Qaanaaq (photos

Dolores Gonzalez)

We make our way towards Harward Oer, an archipelago that

seems to offer several little bays where we might find a safe

mooring, maybe even for the winter. It is a natural harbour,

8 miles long, protected by an island to the N and S. Our hopes

are exhausted: there are several good moorings, well protected

from the sea and the ice.

To our surprise, the flora is abundant. It is late in the

season, the different plants are pulling back into their roots.

Between the rocks, the ice and the snow, these little green

valleys offer a hospitable contrast. It is certainly no coincidence

that humans have installed themselves here. 4families live

in the little village of Qeqertat. They prefer the calm lifestyle

close to nature over the busy 'city' life. Still there is

regular contact to Qaanaaq (the 'big' city).

Map of the region (© Kort & Matrikelstyrelsen, Miljoministeriet,

Danmark)

Maybe it is here that where we will install ourselves for

the winter. Except for absence of an Internet connection,

all the essential qualities can be found here. It starts by

a good mooring, protected from the sea and the ice but not

to closed in so we can still profit from the wind. And even

though the language barrier was there, the first contact with

the people of Qeqertat was warm and friendly.

Nanuq mooring at Harward Oer, maybe our winter camp. The village

of Qeqertat seen from the W (photos Kalle Schmidt)

As for now we're heading back to Qaanaaq. Once more, we're

mooring in the red waters of Kangerdharssuk, protected from

the S wind blowing with up to 30 knots. Summer is over. Like

the migratory birds follow the flow of the seasons, it is

time for some of us to head S. The small twin engine only

flies once a week. Behind stays a small crew and exciting

adventure to come!

|  Moorings::

Moorings::

ATTENTION : sailing to the E of Qaanaaq requires a

special permission. Ask at the Kommunia for help. It

is also recommended to look out for any hunters on the

water, as to avoid disturbing them in their activities.

Kangerdharssuk (77°33'N 68°35'W): anchorage

in 15m sandy/muddy ground. Good hold to the S of the

delta. There is just enough space to swing around the

anchor with reasonable distance to the shore (20-40m).

Good protection except from the N to E. In SE gales

ice drifts into the bay. In this case; a temporary anchorage

may be found on the opposite shore of the fjord below

the mountains at the S end of the delta - very steep

but good hold. Rich flora. There are a few huts used

by local hunters and rests of a disused village. Easy

access to the Piulip Nunaa ice cap. Alpine landscape.

Harward Oer (77°29.5'N 66°29.3'W): the anchorage

is situated 2.5 miles to the E of Qeqertat. Good hold

in sandy/muddy ground. Protected from the ice and the

heavy sea in all directions, but not sheltered from

the wind because of the low surroundings. Stay in the

middle to cross the bay that separates the N and the

S island. Depths not less than 10m. For the approach

from the W: Round the S of the little islets (77°29N

66°42W) close to the village of Qeqertat. Access

to the mooring from the N. 45min hike to the highest

point of the archipelago (numerous little fresh water

lakes).

Harward Oer (77°30.4'N 66°24.6'W): excellent

mooring in a closed bay 4M to the E of Qeqertat. Depths

between 8 and 25m. Good hold in sandy/muddy ground.

The best protection from southerly winds can be found

to the S of the bay, just to the W of the entry passage

(moor in 15m depth and tie two land lines to the rocks

to the S). Keep clear of the drying rocks all around

the shore at a distance of 20-40m.

Caution: underwater rocks to the SW of the entrance,

aprox 50m from the shore. Green landscape. 15min hike

towards the E to a high point with a view onto the vast

end of the fjord.

Info:

Communication in the region on VHF channel 10. |

|